Introduction

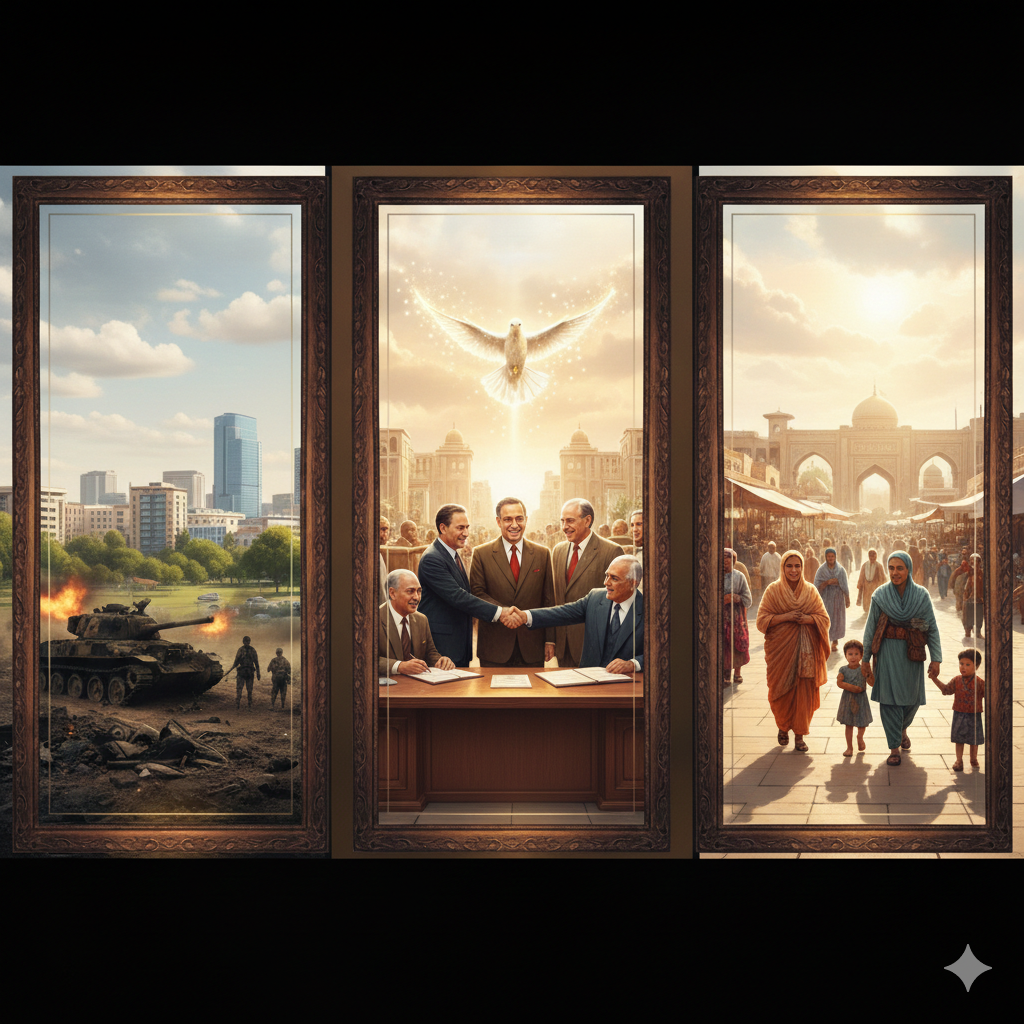

The Tashkent Agreement occupies a significant place in the diplomatic history of South Asia. Signed on 10 January 1966 between India and Pakistan, the agreement marked a formal conclusion to the Indo-Pak War of 1965 and aimed at restoring peace between the two newly independent nations. Mediated by the Soviet Union, the agreement reflected Cold War geopolitics as well as the urgent regional need for stability.

Rather than merely being a ceasefire document, the Tashkent Agreement represented an attempt to reset bilateral relations after a costly military confrontation. Understanding the circumstances that led to this agreement and examining its provisions offers valuable insight into India’s early foreign policy challenges, Pakistan’s strategic calculations, and the growing influence of global powers in South Asian affairs.

Background: Indo-Pak Relations Before 1965

Legacy of Partition

The roots of the 1965 conflict lie in the unresolved issues left by the Partition of 1947. The division of British India created two sovereign states but also left behind deep territorial, political, and emotional disputes—most notably over Jammu and Kashmir.

Since independence, relations between India and Pakistan had been characterized by mistrust, sporadic violence, and competing national identities. The first Indo-Pak war (1947–48) had already hardened positions on Kashmir, while refugee crises and border tensions continued to strain ties.

Kashmir as a Persistent Flashpoint

For Pakistan, Kashmir symbolized an unfinished agenda of Partition. For India, it represented territorial integrity and secular nationalism. Diplomatic efforts during the 1950s failed to resolve this dispute, leaving both countries increasingly reliant on military preparedness.

Immediate Circumstances Leading to the Tashkent Agreement

Operation Gibraltar and Escalation of Conflict

In 1965, Pakistan launched Operation Gibraltar, sending infiltrators into Indian-administered Kashmir with the objective of provoking a local uprising. This miscalculation triggered a strong Indian military response, leading to full-scale war across the international border.

India expanded operations into Punjab and Rajasthan sectors, while Pakistan countered with armored offensives. The conflict rapidly escalated beyond Kashmir.

Military Stalemate

Despite intense fighting, neither side achieved decisive victory. Both countries suffered significant casualties, infrastructure damage, and economic strain. The war exposed limitations in military logistics and preparedness on both sides.

This strategic deadlock created conditions favorable for external mediation.

Role of International Pressure

United Nations Intervention

Alarmed by the risk of prolonged conflict, the United Nations called for an immediate ceasefire, which came into effect on 23 September 1965. However, ceasefire alone could not resolve underlying tensions.

Cold War Context and Soviet Mediation

The United States, previously a major arms supplier to Pakistan, suspended military aid to both countries, weakening Pakistan’s position. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union saw an opportunity to expand its diplomatic influence in South Asia.

Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin invited Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and Pakistani President Ayub Khan to Tashkent (now in Uzbekistan) to negotiate a peace settlement.

For India, Soviet mediation was acceptable due to Moscow’s relatively balanced stance. For Pakistan, it offered an alternative after declining Western support.

Domestic Pressures on Both Countries

India’s Internal Challenges

India faced food shortages, economic constraints, and the task of consolidating national unity after war. Prime Minister Shastri also had to balance military morale with diplomatic realism.

Pakistan’s Political Calculations

President Ayub Khan confronted domestic criticism over the war’s outcome. Pakistan’s leadership sought diplomatic gains to compensate for military stalemate, particularly regarding Kashmir.

These internal pressures made compromise inevitable.

The Tashkent Agreement: Major Highlights

The agreement was signed on 10 January 1966 and contained several important provisions:

1. Restoration of Pre-War Positions

Both sides agreed to withdraw their armed forces to positions held before 5 August 1965. This clause emphasized territorial status quo and prevented immediate future conflict.

2. Commitment to Peaceful Relations

India and Pakistan pledged to resolve disputes through peaceful means and avoid the use of force. This reaffirmed adherence to the UN Charter.

3. Non-Interference in Internal Affairs

Each country agreed not to interfere in the domestic matters of the other, aiming to reduce covert destabilization.

4. Normalization of Diplomatic Ties

The agreement called for restoration of diplomatic relations, resumption of trade, and re-establishment of communication links.

5. Prisoners of War and Civilian Issues

Both sides agreed to exchange prisoners and facilitate the return of displaced civilians.

6. Future Dialogue Framework

Provision was made for continued discussions at ministerial levels to address outstanding issues, including Kashmir.

Notable Omissions

One striking feature of the agreement was the absence of any explicit reference to Kashmir. This disappointed Pakistan, which had hoped for internationalization of the issue. India, however, viewed this omission as a diplomatic success, reinforcing its position that Kashmir was a bilateral matter.

Significance of the Tashkent Agreement

Short-Term Stabilization

The agreement successfully prevented immediate renewal of hostilities and restored formal diplomatic engagement.

Strengthening India’s Diplomatic Standing

India demonstrated commitment to peaceful resolution while maintaining territorial integrity. Its refusal to concede on Kashmir enhanced its negotiating credibility.

Expansion of Soviet Influence

The USSR emerged as a significant mediator in South Asia, marking a shift from Western dominance in regional diplomacy.

Limits of Peace Agreements

Despite its intentions, the Tashkent Agreement failed to address structural causes of conflict. Subsequent wars in 1971 and later crises revealed the fragility of such settlements.

Criticism and Domestic Reactions

In India, some critics argued that the agreement surrendered military gains without extracting political concessions. In Pakistan, Ayub Khan faced accusations of diplomatic failure.

The sudden death of Prime Minister Shastri in Tashkent further intensified emotional responses in India.

Critical Evaluation

While the Tashkent Agreement succeeded in halting hostilities, it remained largely tactical rather than transformational. It addressed immediate military disengagement but avoided deeper political reconciliation.

The agreement highlighted a recurring pattern in Indo-Pak relations: externally mediated ceasefires followed by unresolved core disputes. It also illustrated how Cold War geopolitics shaped regional outcomes.

Nevertheless, Tashkent established a precedent for bilateral dialogue and demonstrated that diplomacy could temporarily override militarism.

Conclusion

The Tashkent Agreement emerged from a complex interplay of military stalemate, international pressure, and domestic necessity. Its provisions emphasized peace, withdrawal, and normalization, but its limited scope prevented lasting resolution.

Although it did not bring enduring harmony, the agreement remains a landmark in India’s diplomatic history. It underscores the importance of dialogue even amid deep rivalry and offers enduring lessons on conflict management in South Asia.

For students of international relations, the Tashkent Agreement serves as a case study in crisis diplomacy, third-party mediation, and the challenges of post-colonial statecraft.