Introduction

In economics, the concept of elasticity of demand is one of the most fundamental tools for understanding consumer behavior and market dynamics. It measures how sensitive the quantity demanded of a good is to changes in various factors such as price, income, and the prices of related goods. This concept plays a crucial role in both theoretical and applied economics, influencing business decisions, government policies, and economic analysis. Understanding elasticity helps economists and policymakers predict consumer responses, estimate revenue changes, and design effective pricing and taxation policies.

Definition of Elasticity of Demand

Elasticity of demand can be defined as the degree of responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a commodity to a change in one of the variables on which demand depends — mainly the price of the commodity, the income of the consumer, or the prices of related goods.

Mathematically, elasticity of demand is expressed as:

[

E_d = \frac{% \text{ change in quantity demanded}}{% \text{ change in price}}

]

Where,

- ( E_d ) = Elasticity of demand

- ( % \text{ change in quantity demanded} = \frac{\Delta Q}{Q} \times 100 )

- ( % \text{ change in price} = \frac{\Delta P}{P} \times 100 )

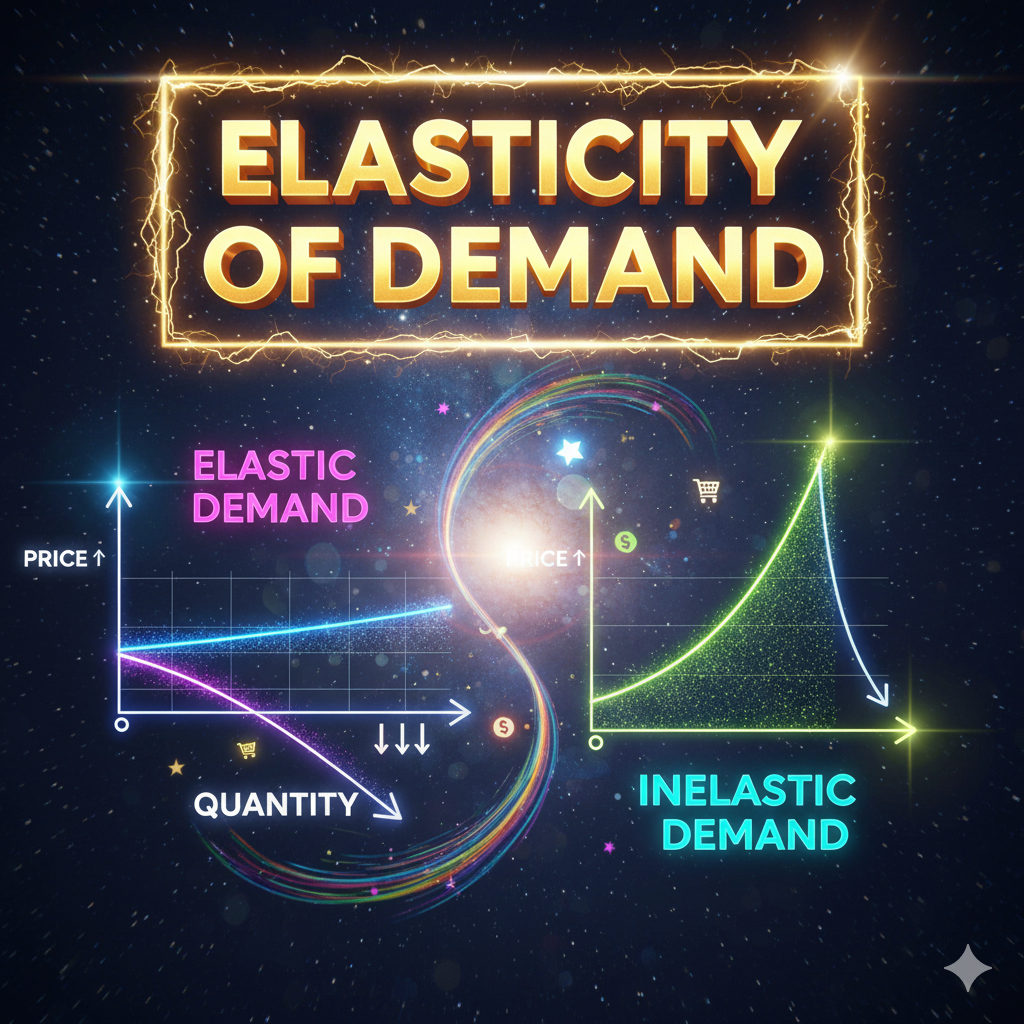

If the change in quantity demanded is greater than the change in price, demand is said to be elastic. If it is less, demand is inelastic.

Thus, elasticity measures the sensitivity or responsiveness of demand to its determinants.

Types of Elasticity of Demand

- Price Elasticity of Demand (PED)

It measures the responsiveness of quantity demanded to a change in the price of the commodity.

[

E_p = \frac{\text{Percentage change in quantity demanded}}{\text{Percentage change in price}}

]- Elastic demand (E > 1): Small change in price leads to a large change in quantity demanded.

- Inelastic demand (E < 1): Quantity demanded changes less than proportionately to price.

- Unitary elastic demand (E = 1): Quantity demanded changes proportionately to price.

- Perfectly elastic demand (E = ∞): Infinite response to any price change.

- Perfectly inelastic demand (E = 0): No change in demand despite price change.

- Income Elasticity of Demand (YED)

It measures the responsiveness of demand to a change in consumer income.

[

E_y = \frac{% \text{ change in quantity demanded}}{% \text{ change in income}}

]- Positive for normal goods.

- Negative for inferior goods.

- Greater than one for luxury goods.

- Cross Elasticity of Demand (CED)

It measures how the quantity demanded of one good responds to the change in the price of another related good.

[

E_c = \frac{% \text{ change in quantity demanded of A}}{% \text{ change in price of B}}

]- Positive for substitute goods (tea and coffee).

- Negative for complementary goods (car and petrol).

- Advertising or Promotional Elasticity of Demand

It measures the responsiveness of demand to changes in advertising expenditure or promotional efforts.

Determinants (Factors Affecting Elasticity of Demand)

Several factors determine how elastic or inelastic the demand for a product is. These factors vary across goods, time periods, and income levels.

1. Nature of the Commodity

- Necessities: Goods essential for survival such as salt, rice, or medicines have inelastic demand because consumers buy them irrespective of price changes.

- Luxuries: Items like air conditioners, perfumes, and designer clothing have elastic demand as consumers can postpone or reduce their consumption when prices rise.

2. Availability of Substitutes

- The more substitutes a commodity has, the more elastic its demand becomes.

For example, tea and coffee are close substitutes; hence, a rise in tea prices may increase coffee consumption. - If a product has no substitutes (like electricity in certain areas), demand tends to be inelastic.

3. Proportion of Income Spent

- If a commodity takes a small portion of the consumer’s income (like salt or matches), demand is less sensitive to price changes (inelastic).

- On the other hand, expensive goods that occupy a larger share of income (like automobiles) have elastic demand.

4. Possibility of Postponement

- Goods whose consumption can be delayed (e.g., smartphones, furniture) tend to have elastic demand.

- Essential goods like medicines or food items have inelastic demand because they cannot be postponed.

5. Time Period

- In the short run, demand is often inelastic because consumers need time to adjust consumption habits.

- In the long run, demand becomes more elastic as consumers find substitutes or adjust behavior.

6. Habits and Addictions

- Habit-forming goods (like cigarettes or alcohol) show inelastic demand because addicted consumers continue purchasing even with price hikes.

7. Range of Uses

- Commodities used for multiple purposes (like electricity or water) tend to have elastic demand, as price changes affect total consumption across uses.

8. Consumer Awareness and Information

- If consumers are aware of price differences among brands, they tend to shift easily, increasing elasticity.

- Lack of awareness or brand loyalty makes demand inelastic.

9. Joint Demand

- Goods used together (like printers and ink cartridges) exhibit inelastic demand, as consumers require both simultaneously.

10. Market Definition

- Broadly defined goods (like food) have inelastic demand.

- Narrowly defined goods (like apples or chocolates) show higher elasticity.

Measurement of Elasticity of Demand

Economists have developed various methods to measure elasticity:

- Percentage Method

[

E_d = \frac{% \text{ change in quantity demanded}}{% \text{ change in price}}

] - Total Expenditure Method (Marshall’s Method)

- If total expenditure (P × Q) remains constant despite price change → Unitary Elasticity

- If total expenditure increases when price falls → Elastic Demand

- If total expenditure decreases when price falls → Inelastic Demand

- Point Method (Geometric Method)

Used on a demand curve to measure elasticity at a specific point.

[

E_d = \frac{Lower Segment of the Demand Curve}{Upper Segment of the Demand Curve}

] - Arc Elasticity Method

Used to measure elasticity over a range of prices.

[

E_d = \frac{(Q_2 – Q_1)}{(Q_2 + Q_1)} \div \frac{(P_2 – P_1)}{(P_2 + P_1)}

]

Practical Importance of Elasticity of Demand

Elasticity of demand has immense practical and policy relevance. It guides businesses, governments, and consumers in making rational and effective decisions.

1. Importance to Business and Industry

- Pricing Decisions:

Firms can set prices strategically based on elasticity. If demand is inelastic, they may increase prices to raise revenue. If elastic, they lower prices to attract more buyers. - Revenue Estimation:

Knowledge of elasticity helps firms predict how sales and total revenue will change with pricing adjustments. - Production Planning:

Elasticity guides producers in planning production and inventory. Highly elastic goods require careful supply management to avoid overproduction.

2. Importance to Government

- Taxation Policy:

Governments impose higher taxes on goods with inelastic demand (like petrol, liquor, tobacco) because consumption doesn’t fall drastically even after price rise. - Welfare and Subsidy Programs:

Elasticity helps in deciding which goods to subsidize — necessities with inelastic demand often receive subsidies for social welfare. - Policy Formulation:

Elasticity aids in understanding the potential impact of price controls, tariffs, and trade policies.

3. Importance to Consumers

- Informed Choices:

Understanding elasticity helps consumers compare prices and find substitutes efficiently. - Budget Management:

Consumers can adjust spending patterns according to the elasticity of different goods in response to income or price changes.

4. Importance in International Trade

- The elasticity of export and import demand affects a country’s trade balance.

- According to the Marshall-Lerner Condition, a depreciation in currency will improve the trade balance only if the sum of elasticities of export and import demand is greater than one.

5. Importance in Agricultural Economics

- Agricultural products often have inelastic demand. Hence, bumper harvests can lower prices sharply, reducing farmers’ income. Elasticity knowledge helps design effective price support schemes.

6. Importance in Labor Economics

- The elasticity of demand for labor determines how changes in wages affect employment levels. In sectors where demand for labor is elastic, wage hikes may reduce employment opportunities.

7. Importance in Welfare Economics

- Elasticity helps in measuring consumer welfare changes when prices vary.

- It assists in estimating consumer surplus, a key concept in welfare analysis.

Elasticity and Business Strategy

Elasticity of demand plays a central role in determining a firm’s strategic direction.

- Price Discrimination: Firms charge different prices to different groups if demand elasticities differ (e.g., student discounts).

- Product Differentiation: Companies design unique features or brand images to make demand inelastic.

- Advertising: Marketing can reduce elasticity by increasing brand loyalty.

- Revenue Maximization: Firms analyze elasticity to find the price level that maximizes total revenue.

Theoretical Significance of Elasticity

- Foundation of Demand Theory: Elasticity refines the law of demand by quantifying the relationship between price and quantity.

- Determination of Marginal Revenue: Marginal revenue depends directly on price elasticity of demand.

- Integration with Other Theories: Elasticity interlinks with concepts like utility, indifference curves, and consumer equilibrium.

- Economic Modelling: It provides an analytical tool for predicting responses in both micro and macroeconomic models.

Limitations of Elasticity Concept

- Difficulties in Measurement: Exact data on price and quantity changes may not be available.

- Static Nature: Elasticity provides a snapshot but not dynamic behavioral changes over time.

- Influence of Psychological Factors: Consumer emotions, trends, or social influence may distort measured elasticity.

- Heterogeneous Consumers: Different groups respond differently to the same price changes, making generalization difficult.

Conclusion

The elasticity of demand is a cornerstone of microeconomic analysis. It provides deep insight into how consumers respond to price, income, and related goods’ changes. Understanding this concept allows firms to design optimal pricing strategies, governments to implement rational fiscal policies, and economists to evaluate welfare impacts.

In a world of dynamic markets and evolving consumer preferences, elasticity remains a vital analytical tool that bridges theoretical economics with real-world decision-making. Whether it concerns a business launching a product, a policymaker imposing taxes, or an economist forecasting demand, the elasticity of demand forms the basis of rational economic thought and planning.