Introduction

Self-Help Groups (SHGs) have emerged as one of the most significant grassroots institutions for promoting participatory development in rural India. By organizing poor households—particularly women—into small, informal collectives, SHGs aim to enhance financial inclusion, livelihood opportunities, social empowerment, and community participation in development programmes. Over the past three decades, SHGs have been integrated into major government initiatives related to poverty alleviation, nutrition, sanitation, education, and rural livelihoods. However, despite their widespread penetration, the effectiveness of SHGs in fostering genuine participation in development programmes is often constrained by deep-rooted socio-cultural hurdles. These barriers shape who participates, how decisions are made, and the extent to which empowerment translates into structural change.

Role of SHGs in Participatory Rural Development

SHGs function as platforms for collective savings, credit access, skill development, and social mobilization. Beyond economic activities, they act as intermediaries between the state and rural communities. Government programmes increasingly rely on SHGs for last-mile delivery, awareness generation, beneficiary identification, and community monitoring.

Through regular meetings, shared responsibilities, and peer accountability, SHGs encourage participation from marginalized sections, particularly women. They have played a crucial role in implementing development initiatives related to nutrition, sanitation, health awareness, financial literacy, and livelihood promotion. In theory, SHGs represent a shift from top-down welfare delivery to bottom-up, community-led development.

Socio-Cultural Context of Rural India

Rural Indian society is shaped by traditional norms related to caste, gender, kinship, religion, and hierarchy. These socio-cultural structures influence access to resources, decision-making power, and public participation. While SHGs seek to create egalitarian spaces, they operate within existing social realities.

Patriarchal norms restrict women’s mobility, time availability, and voice in public forums. Caste hierarchies continue to determine social interactions, often leading to exclusion or domination within group dynamics. Literacy levels, social confidence, and customary authority structures further shape participation patterns.

As a result, SHGs often mirror local power relations rather than transforming them entirely.

Gender-Based Socio-Cultural Barriers

One of the most significant hurdles to effective SHG participation is patriarchy. In many rural areas, women’s involvement in SHGs is permitted primarily as an economic necessity rather than as a means of empowerment. Male family members may control decision-making related to savings, loans, and enterprise activities.

Women often face restrictions on attending meetings, traveling for training, or interacting with officials. Domestic responsibilities such as childcare, cooking, and agricultural labor limit the time and energy they can devote to SHG activities. In some cases, women act merely as nominal members, while men exercise de facto control over financial decisions.

These gender norms reduce the transformative potential of SHGs and confine participation to instrumental rather than substantive engagement.

Caste and Social Hierarchies

Caste remains a powerful determinant of participation in rural development institutions. Although SHGs are designed to be inclusive, social stratification often influences group formation and functioning. Marginalized communities may face subtle exclusion, discrimination, or domination within mixed-caste SHGs.

In some villages, upper-caste members assume leadership roles, control access to information, and influence linkages with banks or government officials. Dalit and tribal women may hesitate to speak freely due to fear of social backlash or internalized inferiority.

In areas with strong caste identities, parallel SHGs may emerge along caste lines, limiting collective action across social groups and reducing the broader social impact of SHG-led development.

Cultural Norms and Resistance to Collective Action

Traditional rural society places a high value on conformity and obedience to customary authority, such as village elders or local elites. SHGs, by promoting collective decision-making and questioning existing power structures, sometimes face resistance.

Women asserting financial independence or public voice may be perceived as challenging established norms. This can result in social pressure, gossip, or even coercion to withdraw from SHG activities. In conservative regions, participation in SHGs is tolerated only when it aligns with socially accepted roles.

Such resistance weakens the ability of SHGs to function as agents of social change and limits their participation in transformative development programmes.

Education, Awareness, and Confidence Deficits

Low levels of literacy and awareness among rural women affect the quality of participation in SHGs. Many members lack understanding of financial procedures, government schemes, legal rights, or institutional processes. As a result, decision-making is often dominated by a few relatively educated or confident members.

This uneven participation reduces internal democracy and limits collective ownership of development initiatives. Dependence on external facilitators, NGOs, or government functionaries can also undermine autonomy.

Without sustained capacity-building, SHGs risk becoming passive conduits for scheme implementation rather than active partners in development planning.

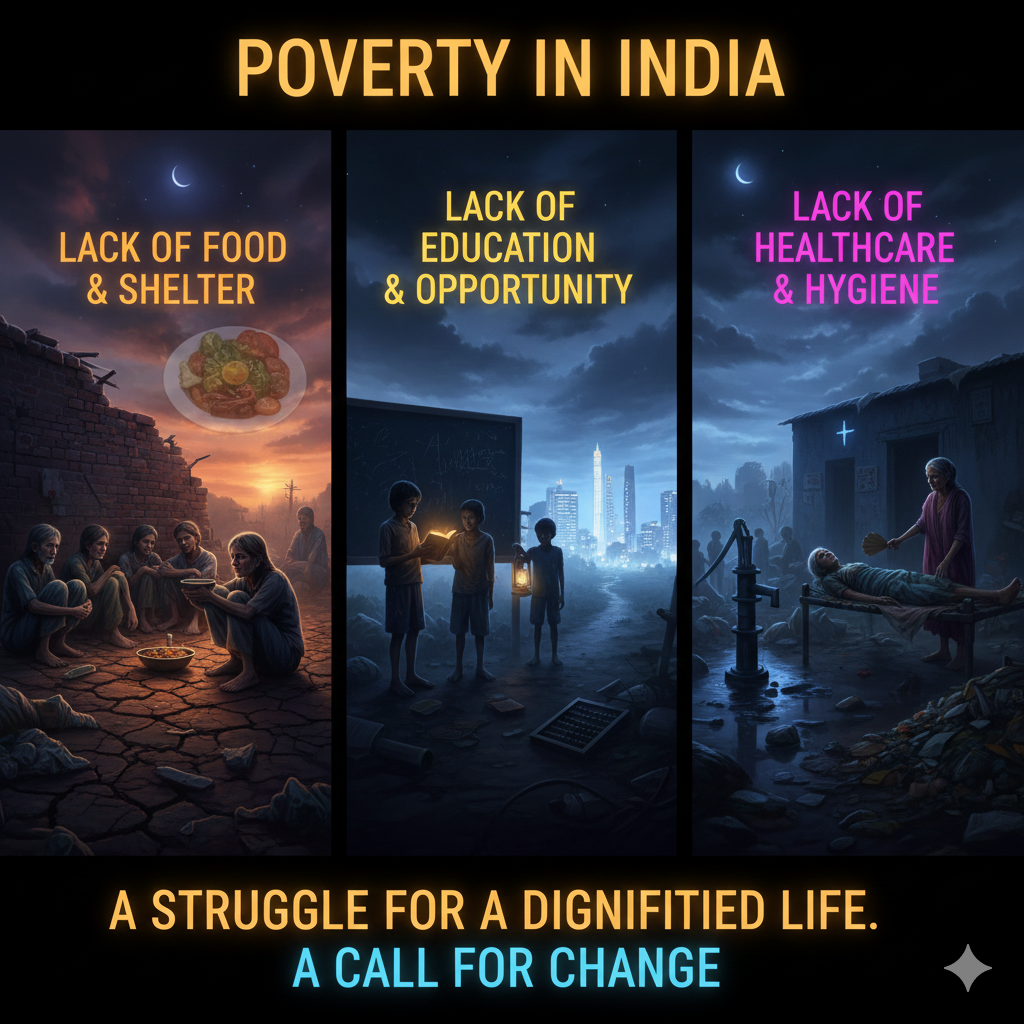

Intersection of Poverty and Cultural Constraints

Economic vulnerability intensifies socio-cultural barriers. Poor households may prioritize immediate survival needs over long-term collective action. Women from extremely poor families may join SHGs primarily for credit access, with limited engagement in broader development activities.

Fear of loan default, social stigma, or conflict discourages open participation. Cultural norms emphasizing risk aversion further constrain innovation and entrepreneurship within SHGs.

Thus, poverty and socio-cultural constraints reinforce each other, limiting the depth of participation in development programmes.

Impact on Participation in Development Programmes

Due to these socio-cultural hurdles, SHG participation in development programmes often remains uneven. While SHGs are effective in improving outreach and implementation efficiency, their role in participatory planning, social accountability, and community empowerment is constrained.

Participation is frequently procedural rather than deliberative. SHGs may assist in beneficiary mobilization or scheme awareness but have limited influence over programme design or monitoring. The transformative potential of SHGs is therefore realized only partially.

Measures to Overcome Socio-Cultural Barriers

Addressing socio-cultural hurdles requires long-term social interventions alongside economic initiatives. Continuous capacity-building, leadership training, and rights-based education are essential to strengthen women’s confidence and agency.

Promoting federations of SHGs can reduce local power imbalances and enhance collective bargaining. Inclusion of marginalized groups must be actively ensured through targeted outreach and safeguards against discrimination.

Engaging men and community leaders in gender sensitization can reduce resistance and foster supportive environments. Linking SHGs with local governance institutions can enhance their legitimacy and influence in development planning.

Conclusion

The penetration of SHGs in rural India has significantly enhanced participation in development programmes, particularly among women and marginalized groups. However, this participation is deeply shaped—and often constrained—by entrenched socio-cultural barriers related to gender norms, caste hierarchies, traditional authority structures, and educational deficits.

While SHGs have succeeded as instruments of economic inclusion and service delivery, their role as agents of transformative participatory development remains incomplete. Overcoming socio-cultural hurdles requires sustained social change, institutional support, and a shift from viewing SHGs merely as implementation tools to recognizing them as platforms for empowerment and democratic participation.

Only when socio-cultural constraints are consciously addressed can SHGs realize their full potential as catalysts of inclusive and participatory rural development.