Introduction

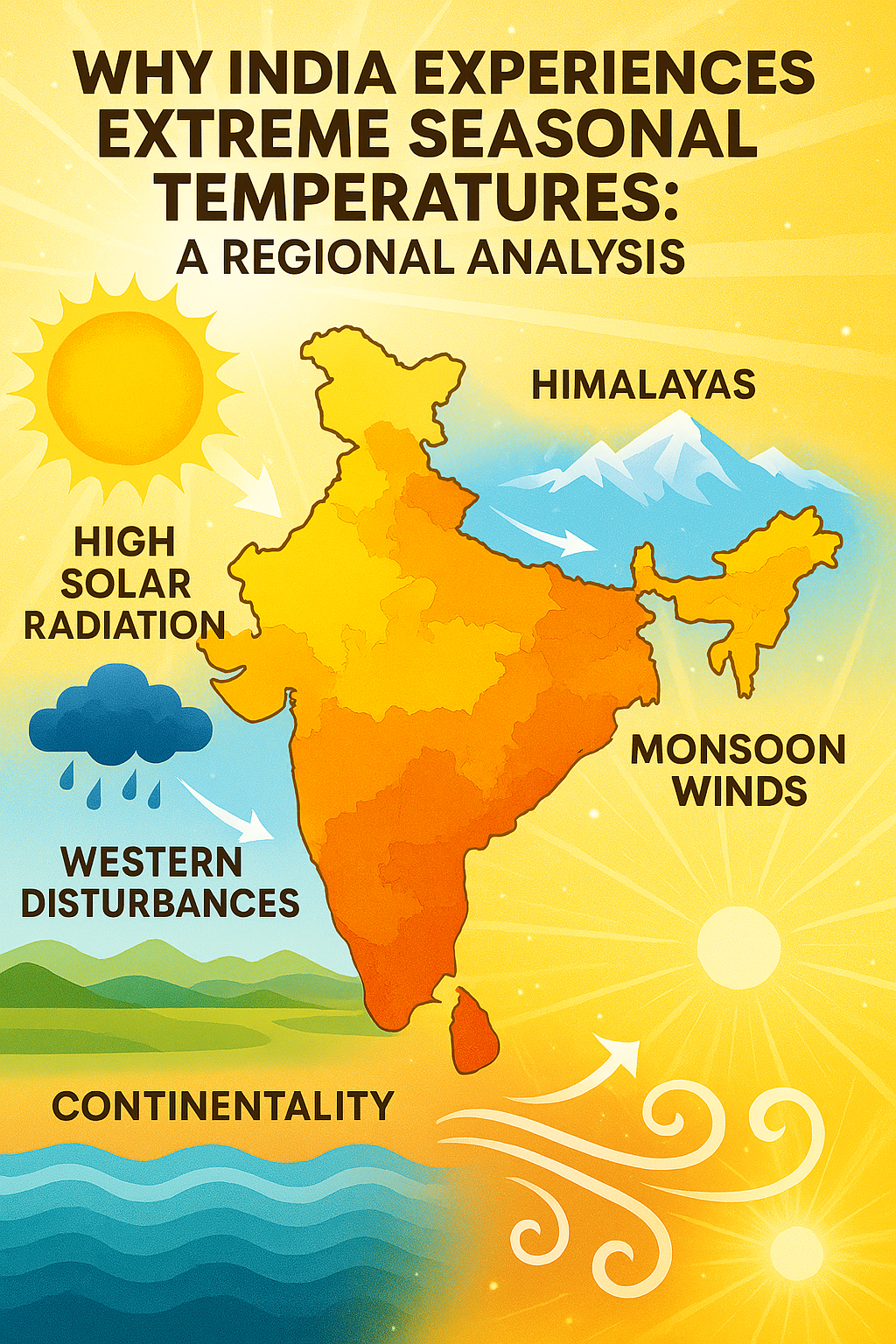

India, known for its diverse geography and climate, experiences a wide range of temperature variations throughout the year. From the snow-capped Himalayas in the north to the tropical coasts in the south, the contrast in climate is striking. This variation becomes particularly noticeable during summer and winter when some regions face scorching heat while others shiver in the cold. But why does such a vast difference occur within a single country?

This article delves deep into the geographical, climatic, and atmospheric reasons behind India’s regional temperature extremes during the summer and winter seasons. The analysis is tailored for academic and educational purposes, ensuring a unique and comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Understanding the Climate Zones of India

Before we explore the reasons for temperature extremes, it’s essential to understand India’s climatic classification. India experiences tropical monsoon climate, but it encompasses multiple sub-climates due to its vast size and varying terrain.

Major Climate Zones:

- Tropical Wet (Humid) – Western coast and northeastern states.

- Tropical Dry – Interior peninsular India and western Rajasthan.

- Subtropical Humid – Indo-Gangetic plains.

- Mountain Climate – Himalayan region.

- Arid and Semi-Arid – Rajasthan, Gujarat, parts of Deccan Plateau.

Each of these zones reacts differently to seasonal shifts due to their location, altitude, proximity to water bodies, and topography, which we will explore in detail.

Key Factors Causing Temperature Variation in India

1. Latitude and Solar Insolation

The latitude of a region determines the angle at which the sun’s rays strike the Earth. India lies between 8°N to 37°N, covering both tropical and subtropical zones.

- Southern India is closer to the equator and receives more direct sunlight year-round. Hence, temperature variation is minimal.

- Northern India, especially the Indo-Gangetic plains and the Himalayan foothills, experience greater variation due to seasonal shifts in the sun’s apparent position.

During summer, northern India gets vertical sun rays leading to high temperatures (often exceeding 45°C). In winter, the sun shifts southward, leading to lower insolation and hence colder temperatures (even dipping below freezing in some northern parts).

2. Distance from the Sea (Continentality)

The ocean has a moderating effect on temperature due to its high specific heat. Therefore:

- Coastal regions (like Mumbai, Chennai, and Kochi) have moderate climates with smaller differences between summer and winter temperatures.

- Inland areas (like Delhi, Jaipur, and Nagpur) experience continental climate, which is marked by hot summers and cold winters due to the lack of maritime influence.

For instance, Mumbai might experience a temperature range from 25°C to 35°C year-round, while Delhi could range from 5°C in January to 45°C in June.

3. Altitude and Topography

Altitude plays a critical role in temperature regulation. The general rule is that temperature decreases by approximately 6.5°C for every 1,000 meters of elevation.

- The Himalayas remain cold throughout the year due to their elevation. Even in peak summer, places like Leh or Gulmarg remain relatively cool.

- Hill stations like Shimla, Mussoorie, and Nainital also experience cooler temperatures year-round compared to nearby plains.

Thus, places located at higher altitudes experience lesser summer heat and more intense winter cold, especially due to phenomena like temperature inversion in valleys.

4. Role of the Himalayas

The Himalayas act as a climatic barrier for India:

- In winter, they block the icy winds from Central Asia, preventing extreme cold from spreading into the Indian subcontinent. However, northern plains still experience cold waves due to proximity.

- In summer, the range does not block heat, and the Indo-Gangetic plains often become a heat trap, leading to scorching summers.

Additionally, the Himalayan region sees snowfall, contributing to sub-zero winter temperatures in northern states like Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand.

5. Western Disturbances and Cold Waves

In winter, Western Disturbances—low-pressure systems originating from the Mediterranean—bring cold winds and snowfall to North India.

- These systems affect Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and even Rajasthan, leading to a sudden drop in temperatures.

- Cold waves follow the passage of these systems, particularly impacting northern and central India.

In contrast, southern India remains largely unaffected due to its location and topography, hence witnessing milder winters.

6. Thar Desert and Heat Waves

The Thar Desert in Rajasthan contributes to extreme summer temperatures due to:

- Intense solar heating of sandy surfaces.

- Low humidity and vegetation.

- Absence of cloud cover.

As a result, places like Phalodi and Barmer have recorded temperatures above 50°C, making them some of the hottest places in India.

This heat also contributes to loo winds, hot dry winds that blow across north and central India during peak summer.

7. Wind Patterns and Monsoons

India’s seasonal wind system plays a vital role in temperature distribution.

- Summer: Southwest monsoon winds bring cooling rains, reducing temperature temporarily.

- Winter: Northeastern winds are dry and cold, increasing the chill factor in northern India.

These wind shifts directly impact regional temperatures—for instance, Kerala gets monsoon rains by early June, which cools the region, while Delhi has to wait till July for similar relief.

8. Urban Heat Islands

Urban areas like Delhi, Bengaluru, and Hyderabad face higher temperatures compared to surrounding rural regions due to:

- Concrete surfaces absorbing more heat.

- Pollution and vehicular emissions.

- Lack of vegetation and green cover.

This effect intensifies both summer heat and winter inversions, especially in metropolitan cities.

Case Studies: Regional Comparison

1. Rajasthan vs. Kerala

- Rajasthan: Inland, arid, sandy terrain. Summers reach 48–50°C, winters drop to near 5°C.

- Kerala: Coastal, humid, and tropical. Temperatures range between 22–35°C year-round with little variation.

2. Delhi vs. Mumbai

- Delhi: Continental, extreme variation. Winter lows: 3–5°C; Summer highs: 45–47°C.

- Mumbai: Coastal. Winter lows: 18–20°C; Summer highs: rarely exceed 35°C.

3. Srinagar vs. Chennai

- Srinagar (J&K): Sub-zero winters with heavy snowfall. Summers are mild (15–30°C).

- Chennai (Tamil Nadu): Minimal variation—summers range from 30–42°C; winters stay above 20°C.

Impact of Temperature Extremes

1. Human Health

- Cold waves lead to respiratory illnesses, especially among the elderly and children.

- Heat waves cause dehydration, heatstroke, and increased mortality.

2. Agriculture

- Frost during winters affects crops like wheat and mustard in North India.

- Heat stress in summer impacts crop productivity and irrigation demands.

3. Water Resources

- Melting snow in the Himalayas during summer feeds rivers like Ganga and Yamuna.

- Extreme summer heat dries up surface water in central and western India.

Climate Change and Amplified Extremes

Recent studies indicate that climate change is exacerbating temperature variations:

- Longer and more intense heatwaves are being recorded, especially in North India.

- Winters are becoming shorter but more erratic, with intense cold spells followed by sudden warming.

- Urban areas are witnessing amplified temperature variations due to loss of green cover and poor planning.

This adds another layer of complexity to regional climate patterns.

How India Adapts to Temperature Extremes

1. Architectural Solutions

- In hot regions, houses are built with thick walls, high ceilings, and courtyards (e.g., in Rajasthan).

- In cold regions, homes use insulation and low roofs to retain heat (e.g., in Himachal Pradesh).

2. Clothing

- People adapt with region-specific attire: woolens in the north, cottons in the south.

3. Agricultural Cycles

- Cropping patterns are designed according to seasonal temperature fluctuations (Rabi and Kharif).

Conclusion

India’s extreme temperature variations are a direct result of its diverse geography, altitude, latitudinal extent, and dynamic atmospheric conditions. From the freezing winters in the Himalayas to the searing heat of the Thar Desert, every region responds uniquely to seasonal changes. Understanding these patterns is crucial for disaster preparedness, agricultural planning, and climate-resilient development.

As climate change continues to intensify, it becomes even more important to study and mitigate the risks posed by these extremes. With informed policies, scientific research, and local adaptation, India can turn its climatic diversity into a strength rather than a vulnerability.