Introduction

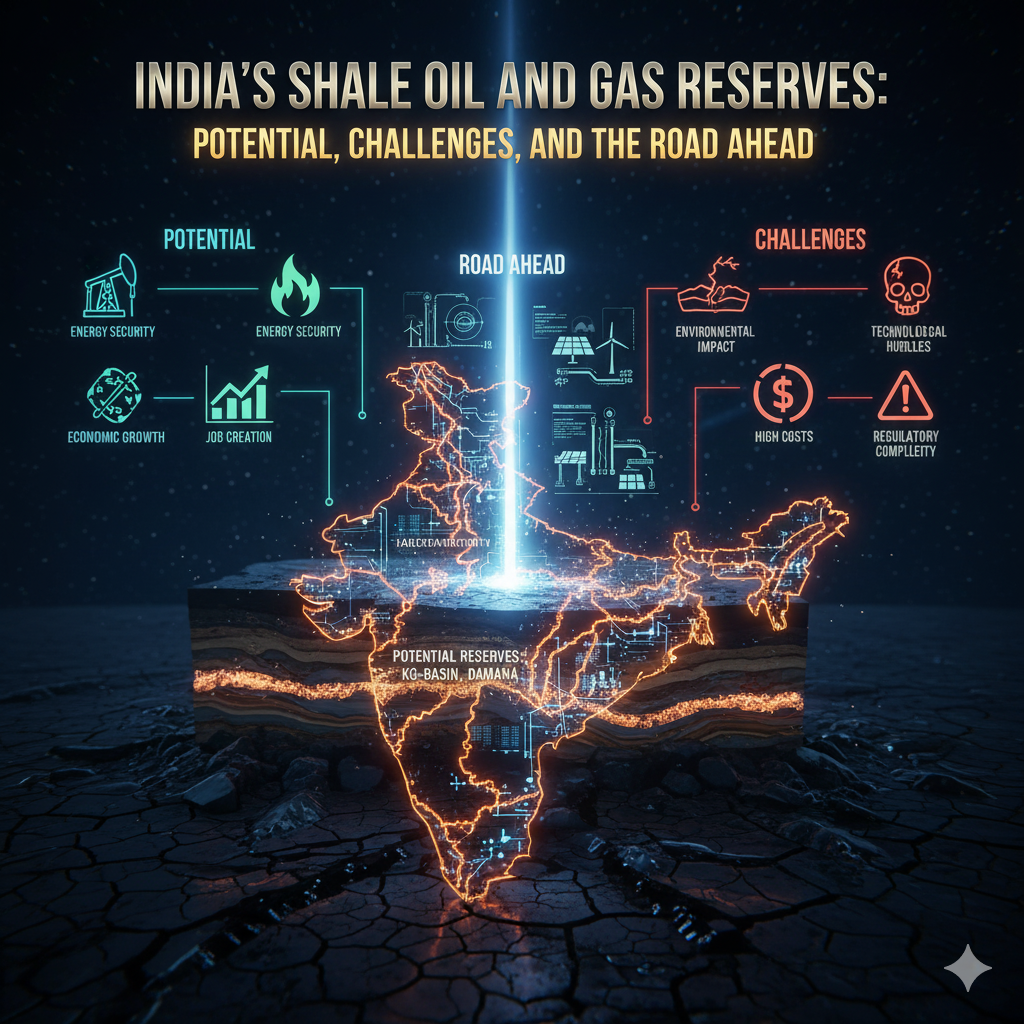

Energy security is one of the cornerstones of India’s economic and strategic policy. As the world transitions from fossil fuels to renewable energy, India faces the dual challenge of meeting its growing energy demands and reducing its dependence on imports. In this context, the discovery of substantial shale oil and gas reserves in India has generated optimism that the country could achieve greater energy self-sufficiency.

Shale resources, which are unconventional hydrocarbons trapped in fine-grained sedimentary rock formations, have transformed the energy landscape in countries like the United States, leading to what is termed as the “shale revolution.” However, despite significant estimates of shale reserves in India, their commercial exploitation has remained limited. This situation raises critical questions about the availability, feasibility, environmental impact, and policy readiness for tapping shale oil and gas in India.

1. Understanding Shale Oil and Gas

1.1 Definition and Characteristics

- Shale oil refers to liquid hydrocarbons trapped within shale rock formations, extracted using techniques like hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling.

- Shale gas is natural gas (primarily methane) found in the same formations. Unlike conventional gas, which flows freely, shale gas requires high-pressure fracturing to release it.

These resources are classified as “unconventional hydrocarbons” because their extraction involves more complex and capital-intensive processes compared to conventional oil and gas.

1.2 Global Perspective

The United States pioneered the extraction of shale gas and oil, leading to a dramatic increase in domestic energy production and a decline in global oil prices after 2010. Other countries such as China, Argentina, and Canada have also ventured into shale energy development.

India, by contrast, has remained cautious due to technological, environmental, and policy-related challenges.

2. Shale Oil and Gas Availability in India

2.1 Estimated Reserves

Various studies by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), ONGC, and the Directorate General of Hydrocarbons (DGH) indicate that India possesses significant shale reserves, though the exact extent remains uncertain due to limited exploration.

| Basin | States Covered | Estimated Shale Oil (billion barrels) | Estimated Shale Gas (trillion cubic feet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cambay Basin | Gujarat | 2.3 | 96 |

| Krishna-Godavari Basin | Andhra Pradesh, Telangana | 2.7 | 45 |

| Cauvery Basin | Tamil Nadu | 1.1 | 5 |

| Damodar Basin | Jharkhand, West Bengal | 0.9 | 35 |

| Assam-Arakan Basin | Assam | 0.8 | 8 |

(Data: U.S. EIA, 2015; DGH estimates)

Together, these basins could potentially meet a significant portion of India’s oil and gas demand for nearly 25 years, if commercially viable extraction becomes possible.

2.2 Key Geological Basins

- Cambay Basin (Gujarat) – Most promising due to thick organic-rich shale formations and existing oil infrastructure.

- Krishna-Godavari Basin (Andhra Pradesh) – Offers substantial reserves but lies in ecologically sensitive coastal regions.

- Damodar Basin (Jharkhand and West Bengal) – Contains both coal and shale gas, but faces land and water availability issues.

- Assam-Arakan Basin (Northeast India) – Geologically complex and located in seismically active zones.

3. Potential Benefits of Shale Energy Development

3.1 Energy Security

India imports over 85% of its crude oil and 50% of its natural gas requirements. Shale development could significantly reduce this dependence, enhancing strategic autonomy and reducing vulnerability to global price shocks.

3.2 Economic Growth

- Development of a shale industry would attract foreign direct investment (FDI) and generate employment in drilling, logistics, and refining sectors.

- Local energy production could stabilize prices and improve the balance of payments by reducing import bills.

- Ancillary industries such as chemical manufacturing and pipeline infrastructure would also benefit.

3.3 Technological Advancement

Exploring shale resources would promote technological innovation in drilling, seismic imaging, and environmental management—skills that could be applied to other sectors of India’s energy economy.

3.4 Rural Development

Many shale-rich regions are in rural and underdeveloped areas. Responsible development could create jobs and infrastructure in these regions, leading to broader socio-economic growth.

4. Challenges and Issues in Exploiting Shale Resources

Despite its potential, India’s shale energy program faces multiple technical, environmental, social, and policy hurdles that have hindered progress.

4.1 Technological Challenges

- Lack of Advanced Drilling Equipment: Shale extraction requires sophisticated horizontal drilling and multi-stage hydraulic fracturing technologies, which are cost-intensive and import-dependent.

- Limited Data and Exploration: India’s sedimentary basins have not been studied in depth for shale potential; core samples and geological mapping are still inadequate.

- High Decline Rates: Shale wells deplete faster than conventional wells, requiring continuous drilling to maintain output, which increases production costs.

4.2 Economic Viability

- Shale extraction in India is costlier than in the U.S. due to higher population density, complex land acquisition processes, and lack of domestic service infrastructure.

- The low global oil and gas prices over the past decade have made shale projects economically unattractive.

- Absence of fiscal incentives or subsidies for shale development further discourages investment.

4.3 Environmental Concerns

- Water Consumption: Hydraulic fracturing consumes large quantities of water—an acute issue in water-stressed regions like Gujarat and Rajasthan.

- Groundwater Contamination: Chemicals used in fracking fluids pose a risk to groundwater quality.

- Seismic Risks: Injection of wastewater into deep wells can induce micro-earthquakes, a concern in seismically active regions like Assam and the Himalayas.

- Land Degradation: Shale operations require significant land area, leading to deforestation and biodiversity loss in ecologically fragile zones.

4.4 Social and Legal Issues

- Land Acquisition: Acquiring land for drilling is contentious in India due to dense population and multiple ownership claims.

- Public Opposition: Local communities often resist due to fears of pollution, displacement, and inadequate compensation.

- Regulatory Ambiguity: India lacks a dedicated legal framework for shale hydrocarbons. Current policies under the Petroleum and Natural Gas Rules (1959) and the Hydrocarbon Exploration and Licensing Policy (HELP, 2016) are not tailored for unconventional resources.

4.5 Institutional and Policy Gaps

- The division of authority between central and state governments over land and water complicates project approvals.

- Lack of clear environmental guidelines for fracking leads to policy paralysis.

- There is insufficient coordination among ministries such as Petroleum, Environment, and Water Resources.

5. Government Initiatives and Policy Developments

5.1 Early Steps

- In 2013, the Government of India permitted National Oil Companies (NOCs) like ONGC and Oil India Limited (OIL) to explore shale oil and gas in their existing petroleum exploration blocks.

- Pilot projects were launched in the Cambay, Cauvery, and Damodar basins, but results were not commercially encouraging due to low recovery rates and high costs.

5.2 Hydrocarbon Exploration and Licensing Policy (HELP), 2016

- Introduced a uniform licensing system for both conventional and unconventional hydrocarbons.

- Allowed open acreage licensing, enabling companies to choose blocks based on their own data and interest.

- Shifted to a revenue-sharing model to attract investors.

However, the policy did not specifically address fracking-related environmental safeguards or infrastructure incentives.

5.3 Collaboration with Foreign Partners

ONGC and OIL have entered into technical collaboration with companies from the U.S. and Canada to gain expertise in shale technology. However, large-scale foreign participation remains limited due to regulatory uncertainties and lack of incentives.

5.4 Research and Environmental Studies

The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas has initiated studies with CSIR laboratories and the Central Ground Water Board to assess the environmental impacts of fracking, but a comprehensive framework is still under development.

6. Critical Evaluation: Why Shale Energy Is Not a Priority Yet

Despite its potential, shale development has not become a central component of India’s energy strategy. Several factors explain this cautious approach:

6.1 Competing Priorities

India’s focus is shifting towards renewable energy—particularly solar, wind, and green hydrogen—to meet its Net Zero 2070 commitments. Investing heavily in shale oil, a fossil fuel, may contradict these goals.

6.2 Environmental and Social Sensitivities

Given India’s high population density and water scarcity, large-scale fracking could lead to ecological and social backlash. The environmental cost may outweigh the short-term energy gains.

6.3 Economic Non-Viability

With global oil prices fluctuating and the availability of cheaper LNG imports, the economic case for shale production in India remains weak. Exploration costs are high, and returns are uncertain.

6.4 Technological Dependence

India lacks the domestic technological ecosystem for cost-effective shale development. Reliance on imported equipment and expertise limits scalability and increases risks.

6.5 Regulatory and Data Gaps

Absence of a comprehensive national shale policy, inadequate geological data, and fragmented institutional responsibilities have prevented consistent policy action.

7. The Way Forward: Realistic Path to Harnessing Shale Potential

7.1 Detailed Geological Surveys

- Invest in high-resolution seismic surveys and core sampling to obtain accurate data on shale quality and depth.

- Collaborate with academic and research institutions to improve basin modeling.

7.2 Policy and Regulatory Reforms

- Frame a National Shale Energy Policy focusing on exploration standards, water management, and environmental safeguards.

- Streamline approval processes and promote public-private partnerships (PPP).

7.3 Technological Innovation

- Encourage indigenous R&D in fracking fluids, horizontal drilling, and wastewater treatment.

- Support technology transfer through joint ventures with global leaders.

7.4 Sustainable Water Management

- Promote use of recycled or non-potable water for fracking.

- Establish strict monitoring mechanisms to prevent groundwater contamination.

7.5 Economic Incentives

- Provide tax breaks, exploration subsidies, and royalty adjustments to attract investors.

- Develop infrastructure corridors for transport and storage of shale hydrocarbons.

7.6 Balanced Energy Strategy

India should adopt a dual-track strategy—exploring shale energy to enhance short-term energy security while accelerating its transition towards renewables and cleaner fuels.

8. Conclusion

India’s shale oil and gas reserves represent a significant untapped opportunity to bolster its energy independence. However, the complex interplay of technological limitations, environmental risks, economic unviability, and policy uncertainty has kept shale energy on the periphery of India’s energy agenda.

While the potential to meet the nation’s energy needs for a quarter-century exists, the pathway to realizing this potential is fraught with challenges. In the context of India’s climate commitments and sustainable development goals, a cautious and evidence-based approach is essential.

The future of shale energy in India will depend on how effectively the country can balance energy security with environmental sustainability, ensuring that the pursuit of progress does not compromise ecological integrity. Shale energy should therefore be viewed as a transitional opportunity—a bridge between conventional hydrocarbons and the renewable energy future that India envisions.