Introduction

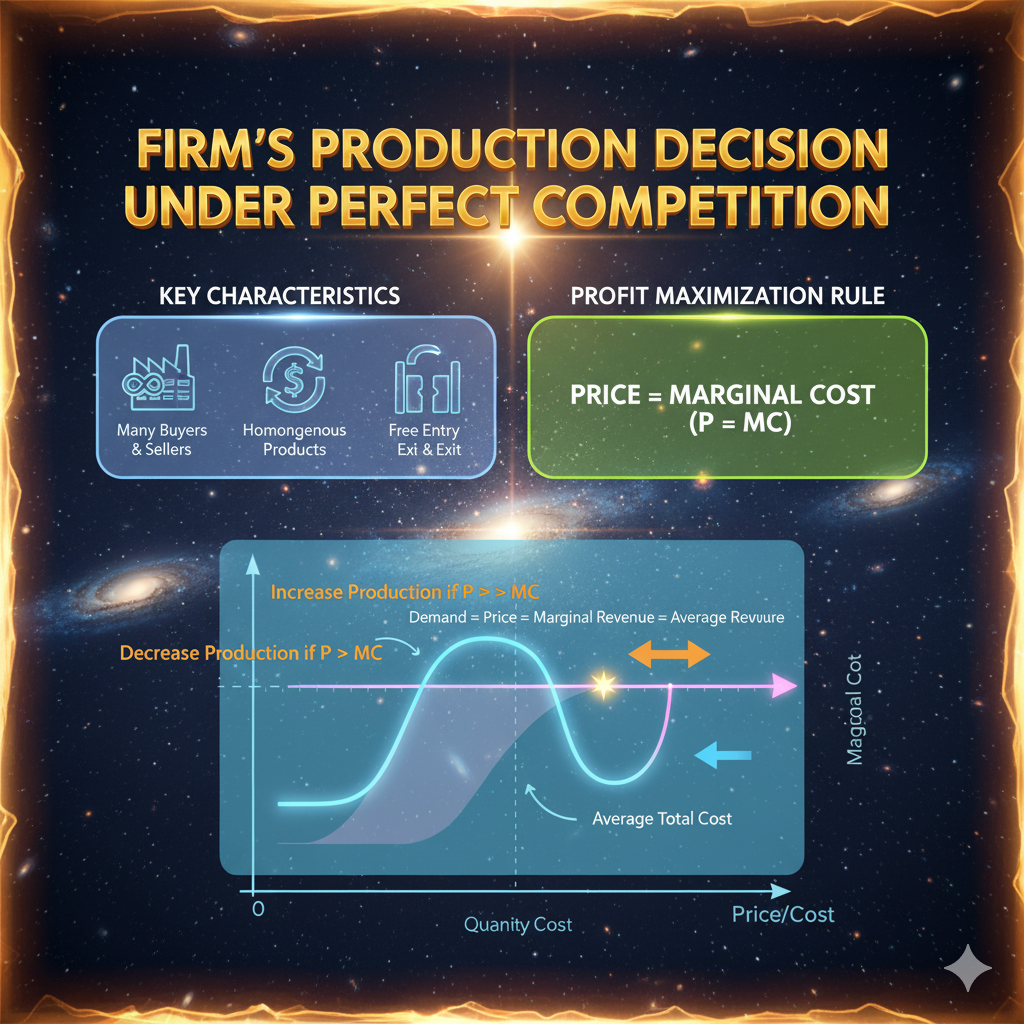

In economics, the concept of perfect competition represents an ideal market structure where numerous firms operate freely, selling identical products, and where none possesses the power to influence the market price. Every firm under perfect competition is a price taker, not a price maker. This means that the firm has no control over the price of the product; the price is determined purely by market demand and supply.

Thus, in such a situation, the firm’s primary decision is not about what price to charge but about how much quantity to produce at the prevailing market price. This decision determines the level of output that maximizes the firm’s profit or minimizes its losses in the short run and ensures survival in the long run.

This essay examines in detail why, under perfect competition, the firm’s only problem is to determine the quantity of production. It will also discuss the assumptions of perfect competition, the price-output relationship, equilibrium of a firm, and the significance of production decisions in this context.

Concept of Perfect Competition

Perfect competition is a type of market structure in which there are a large number of small firms producing a homogeneous product, and the entry and exit of firms are free. Each firm is too small to affect the market price by its own individual actions. The market price is determined by the interaction of total demand and total supply of the industry.

Characteristics of Perfect Competition

- Large Number of Buyers and Sellers

In a perfectly competitive market, there are numerous buyers and sellers. The number is so large that no single buyer or seller can influence the market price. Each firm contributes a negligible portion of the total market supply. - Homogeneous Product

The goods produced by all firms are identical in every aspect. Since there is no difference in quality or features, buyers have no reason to prefer one seller over another. - Free Entry and Exit of Firms

Firms can enter or exit the industry freely based on profit opportunities. In the long run, this ensures that firms earn only normal profit. - Perfect Knowledge of Market Conditions

Both buyers and sellers have complete knowledge about market prices and product quality. This ensures that all transactions happen at the prevailing price. - Price Taker Behavior

Each firm accepts the price determined by the overall market forces of demand and supply. It cannot influence price through its individual production decisions. - Perfect Mobility of Factors of Production

Factors such as labor and capital can move freely from one industry to another, ensuring that resources are efficiently allocated. - Absence of Government Intervention

In a perfectly competitive market, prices are determined by market forces without interference through price controls or restrictions.

Price Determination under Perfect Competition

Under perfect competition, the market determines the price. The price is established at the point where market demand equals market supply.

- The industry (which includes all firms producing the same good) determines the equilibrium price.

- Each individual firm takes this price as given and can sell any quantity of output at that price.

This situation can be represented as follows:

- If a firm raises its price above the market price, buyers will simply purchase from other firms.

- If it lowers the price, it would unnecessarily reduce its profit because it can already sell all it wants at the prevailing price.

Hence, the firm faces a perfectly elastic demand curve at the market price.

The Firm’s Problem: Determining the Quantity of Production

Since the firm has no control over price, its central problem becomes how much quantity to produce in order to maximize profit.

The firm must compare its cost structure and the market price to determine the level of output that yields the maximum profit (or minimum loss).

Profit Maximization under Perfect Competition

The main objective of any firm, regardless of market structure, is profit maximization.

In the case of perfect competition, profit maximization occurs at the point where:

Marginal Cost (MC) = Marginal Revenue (MR)

Here:

- Marginal Revenue (MR) = Market Price (since the price remains constant for every additional unit sold).

- Marginal Cost (MC) = The cost incurred in producing one additional unit of output.

Thus, the firm’s decision revolves around finding the quantity of output where MC = MR.

Equilibrium of the Firm under Perfect Competition

The equilibrium output of a firm under perfect competition can be analyzed in both short-run and long-run perspectives.

1. Short-Run Equilibrium

In the short run, the firm’s objective is to maximize profit or minimize loss at the existing market price. The short-run equilibrium occurs when the following two conditions are met:

- MC = MR

- MC curve cuts the MR curve from below

At this point, the firm determines its equilibrium output.

Depending on the relationship between the market price (P) and average cost (AC), the firm may earn:

- Supernormal profit (P > AC)

- Normal profit (P = AC)

- Loss (P < AC)

Explanation:

- If the market price is greater than the average cost, the firm earns a supernormal profit.

- If the market price equals average cost, the firm earns normal profit.

- If the market price is less than average cost, the firm incurs a loss, but it may still continue production in the short run if it covers its average variable cost.

2. Long-Run Equilibrium

In the long run, firms can enter or exit the industry freely. If firms are earning supernormal profits, new firms will enter the industry, increasing total supply and thereby reducing the market price. Conversely, if firms are incurring losses, some will exit the industry, reducing supply and raising prices.

Ultimately, the process continues until all firms earn normal profit, where:

Price = Marginal Cost (MC) = Average Cost (AC)

At this point, the firm produces the most efficient level of output and achieves equilibrium.

Graphical Representation

In a perfect competition diagram:

- The horizontal line represents the market-determined price.

- The MC curve cuts the MR (price) line at the point of equilibrium.

- The vertical from this intersection to the quantity axis gives the equilibrium output.

- The area between the price line and the average cost curve represents profit or loss.

Relation Between Increasing Production and Increasing Returns

Under perfect competition, as the firm increases production, it can often experience increasing returns to scale or economies of scale in the long run. This happens because:

- Larger production allows better utilization of resources.

- Fixed costs are spread over a larger number of units.

- Specialization and division of labor improve efficiency.

Thus, in the long run, a perfectly competitive firm operates at the minimum point of the long-run average cost curve, representing the most efficient scale of production.

Why the Firm’s Problem is Only to Determine Quantity of Production

- Price is Fixed

The firm cannot influence the price due to the presence of many competitors and homogeneous products. - Profit Depends on Output

Since price is constant, the only variable affecting profit is output. Therefore, the firm must decide how much to produce to maximize profit. - Cost Structure Guides Output Decision

The firm’s decision on output depends on its cost conditions—especially marginal and average costs. The intersection of MC and MR determines the optimal quantity. - No Control Over Market Forces

Since the market determines price through aggregate demand and supply, the firm focuses on adjusting its production rather than market manipulation. - Objective of Efficiency

To survive in the long run, the firm must produce at the lowest possible cost. Thus, determining the right output level is essential for efficiency and competitiveness.

Short-Run vs Long-Run Output Decisions

| Aspect | Short Run | Long Run |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Factors | Some inputs are fixed | All inputs are variable |

| Entry/Exit of Firms | Not possible | Possible |

| Profit Situation | Can be abnormal or normal | Only normal profit |

| Output Decision | MC = MR condition | MC = MR = AC condition |

| Objective | Maximize profit or minimize loss | Achieve normal profit and efficiency |

Practical Importance of the Concept

- Guides Business Policy

Understanding that price is determined by the market helps firms focus on production efficiency. - Encourages Efficient Resource Allocation

Firms will produce up to the point where marginal cost equals market price, ensuring optimal use of resources. - Benchmark for Real Markets

Although perfect competition rarely exists in reality, it serves as a theoretical benchmark for evaluating the efficiency of other market structures. - Supports Policy Formulation

Governments and economists use this model to analyze welfare, consumer surplus, and productive efficiency. - Encourages Technological Improvement

In the long run, to remain competitive, firms must adopt cost-reducing technologies to operate at the lowest point of their cost curves.

Limitations of Perfect Competition

- Unrealistic Assumptions: Real markets rarely meet the strict conditions of perfect competition.

- Lack of Innovation: Firms earn only normal profit, leaving little incentive for research and development.

- Homogeneity of Products: Ignores consumer preferences and brand loyalty.

- No Role for Advertising: In practice, firms use marketing strategies to attract customers, which the model excludes.

Despite these limitations, the concept provides a clear theoretical understanding of how market forces determine equilibrium.

Conclusion

In a perfectly competitive market, the firm is a price taker and not a price maker. The market price is determined by the interaction of overall demand and supply. Consequently, the firm’s problem is limited to deciding the quantity of output it should produce to maximize profit or minimize loss.

The firm achieves equilibrium when its marginal cost equals marginal revenue, and in the long run, this corresponds to the point where price equals average cost. Therefore, under perfect competition, determining the quantity of production is the firm’s only concern since it has no power to influence market price.

This theoretical framework helps economists understand the efficiency and welfare implications of market behavior, offering valuable insights into how free markets allocate resources optimally.